Campaigns and Projects

Safe Water

On the morning of January 9th, 2014, Pam Nixon was expecting a normal day of work at the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. But as soon as she arrived at work, a handful of people started calling the office to complain about a faint, licorice-like smell in the air near the Elk River. Quickly, this trickle of calls turned into a torrent, and Pam’s life — along with the lives of nearly 300,000 people living near Charleston, WV — was turned upside-down.

Over the following months, the 10,000 gallons of coal-processing chemicals which spilled into Charleston’s main supply of drinking water not only cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fix and upended lives, it also highlighted the shocking string of missteps that led to this disaster: no health hazard information on chemicals stored near drinking water was required, rules to prevent spills were ineffective or nonexistent, inspections and enforcement were rare, responses to violations often amounted to no more than a slap on the wrist, and the public wasn't being informed about the threats to our most vital resource — clean and safe drinking water.

Over the following months, the 10,000 gallons of coal-processing chemicals which spilled into Charleston’s main supply of drinking water not only cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fix and upended lives, it also highlighted the shocking string of missteps that led to this disaster: no health hazard information on chemicals stored near drinking water was required, rules to prevent spills were ineffective or nonexistent, inspections and enforcement were rare, responses to violations often amounted to no more than a slap on the wrist, and the public wasn't being informed about the threats to our most vital resource — clean and safe drinking water.

Although we rarely hear about them unless they directly impact us, chemical spills into our waterways and other sources of drinking water are frighteningly common. From 2005 through 2014, industrial facilities self-reported 20,432 chemical spills (an average of over 2,000 spills per year) including major spills of ammonia, benzene, hydrogen sulfide, sulfuric acid, chlorine, hydrogen cyanide, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, toluene, and sodium hypochlorite into the waterways and drinking water supplies we all depend on.

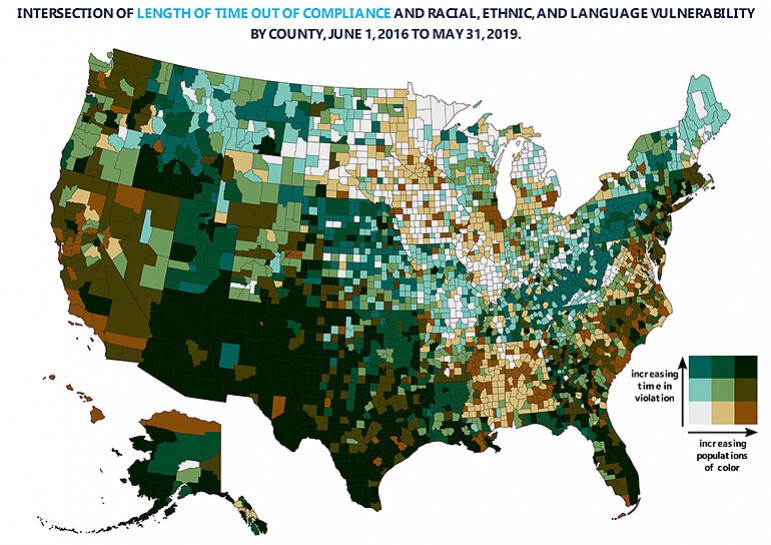

And, although chemical spills are a threat to virtually every American, people of color and low-income communities often face a greater and more frequent threat of drinking water contamination. Data shows a broad, nationwide trend of hazardous spills being more likely to occur in majority non-white counties. In the Elk River Disaster, workers in lower-wage, service industries were more likely to be affected than workers in higher-wage industries.

At EJHA, we believe clean and safe drinking water is a fundamental human right — one that is particularly important during the coronavirus pandemic given the increased need for clean water for sanitizing purposes. That’s why we’re working to prevent chemical spills and protect the water we all depend on. The Elk River chemical spill, along with the thousands of lesser-known spills that have occurred over the last decade, show that more needs to be done to protect our water, so we’re taking action. In a collaborative effort with our partners, we have won two lawsuits prompting new federal rules to prevent or respond to spills such as the Elk River Disaster, and now we’re working to shape those rules to ensure that every community gets the protection it deserves.

We’re bringing together scientists, grassroots community groups, policy experts, and major environmental organizations to work collaboratively and transform how our nation preserves and protects our drinking water. By uniting experts from a wide range of fields, bringing unlikely partners together, and elevating the voices of those living on the front lines — we have both the expertise and the authority to make a difference.

- Understand the danger — by documenting where chemical storage can threaten drinking water, because, shockingly, no one knows where tens of thousands of storage tanks are located.

- Focus on prevention of spills — by requiring owners and operators of chemical tanks to develop public spill-prevention plans and hold routine inspections.

- Set requirements for tanks and protective measures — by requiring tank owners and operators to use safer tank designs, adopt measures to prevent spills from reaching waterways, and post bonds for potential disasters so taxpayers aren’t forced to foot the bill.

- Honor the public’s right to know — by requiring that owners and operators report specific information about chemical storage tanks, including (at least) the location and size of tanks, the chemicals they contain, inspection or audit dates and results, spill prevention plans, with this information available online for public inspection.

- Cover more hazardous substances — by expanding the current list of 330 dangerous chemicals covered by this law to include all of the thousands of harmful chemicals that might threaten our drinking water.

Key Efforts

- Supporting local campaigns in places like Charleston for policies and practices that will protect drinking water and communities by preventing chemical spills;

- Pushing EPA to develop and implement a strong rule to prevent chemical spills from Aboveground Storage Tanks (ASTs);

- Challenging EPA to produce another rule that is 40 years overdue, requiring facilities with chemical ASTs to prepare worst-case spill analysis and response plans.

Resources

- Read our report on how water quality is strongly correlated with race and other factors.

- Learn more about the Safe Drinking Water Act, the principal federal law in the United States intended to ensure the public has adequate access to safe drinking water.

- Connect with a campaign partner in your area.

- Donate to help protect our drinking water.